Japan is known for being a pioneer. To keep it that way, the country not only finalised a series of directives and trade agreements, but is also placing greater focus on digitisation and new technology.

Tradition and modernity have meshed together in Japan in a unique way that is always geared toward advancement. This is reflected in the modern skyline at the port of Kobe.

For German companies, trade with Japan is like a balancing act. This is because they are meeting with business partners from a country more than 9,000 kilometres away, and because Japanese culture is entirely different and shaped by strictly ritualised behaviours and processes (see Behind the Scenes, page 18). Yet Japan also presents itself as a modern, forward-facing country committed to basic freedoms, democracy and human rights. These are the conditions under which Germany and Japan have enjoyed 160 years of growing friendship, with a variety of shared interests and activities at various levels.

“Japan is highly industrialised and owes its wealth to innovative, cutting-edge technology and an efficient economic structure that includes a functioning logistics network. Like in Germany, the most important parts of this are the aumotive industry, mechanical engineering, and the chemical and pharmaceutical sector,” says Jürgen Maurer, correspondent from Trade & Invest (GTAI) in Tokyo, explaining the current role that the world’s fourth largest island nation plays in the global economy. However, due to Japan being an island, this role is entirely different than would be the case in a country in the heart of Europe, for example. This means that over 90 per cent of imports and exports in Japan are processed via maritime routes, and only a small portion is processed via air travel. Yet from an economic perspective, Japan is less dependent on exports than Germany is. The export dependence in Japan is around 14 per cent, compared to about 39 per cent here in Germany.

“Japan owes its wealth to innovative, cutting-edge technology and an efficient economic structure.”

Jürgen Maurer, correspondent from Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI) in Tokyo

Toyota is one of the largest automotive companies worldwide. Japan produces at more than 50 locations in 26 countries. Shown here is the Motomachi Plant in Toyota City (l.). Modern pedestrian bridge in Nagoya Harbour (r.)

Ports are logistics hubs

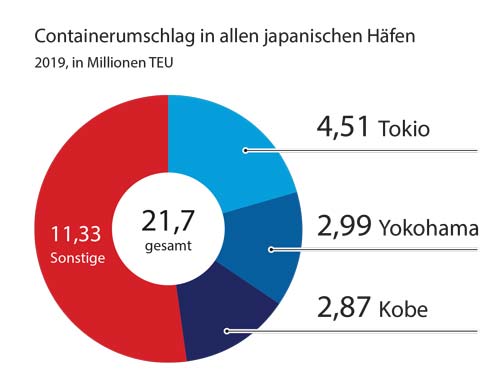

The ports of Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Kobe and Nagoya are important logistics hubs for maritime transport in Japan. “Nagoya Harbour is the largest transshipment site in Japan based on processed freight volume, according to Transportation Ministry statistics,” says Maurer. One reason for this, he says, is that the location is near the Toyota Motors production plant and other major production companies. “Chiba and Yokohama, which serve the Tokyo metro area, rank second and third,” Maurer adds. Based entirely on container transshipment, which amounted to 21.7 million TEU in all Japanese ports in 2019, the ports of Tokyo (4.51 million TEU in 2019), Yokohama (2.99 million TEU) and Kobe (2.87 million TEU) are dominant.

Trailblazing by decree

“To add greater significance to the role of ports in Japan’s supply of goods, the Port and Harbor Law has been updated multiple times since 2000, causing a reduction in port dues and the designation of the ports in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kawasaki, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe as Super Hub ports, among other things,” Maurer explains. Before this law was in place the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Infrastructure and Transportation set the course in 2017 with its “Comprehensive Distribution Policy” to create a robust distribution industry beyond the ports. One primary task stipulated in these directives is making the supply chains more efficient by reinforcing existing sub-systems and integrating hardware and software infrastructures into a corresponding data platform. “Considering potential natural disasters and climate change, these systems should be made more resilient, productive and secure,” says Maurer. Japan is chiefly aiming to integrate the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, Big Data and robotics as cornerstones for implementing this logistics strategy. “For example, they envision being able to construct a smart transportation system with automated warehouses, from which customers can receive deliveries via drone or self-driving vehicles. Two lighthouse projects in this area are an automated distribution centre in Chiba Prefecture where 215 robots are installed, and a digitised logistics chain in the foodstuffs industry initiated by telecommunications company NTT in cooperatiion with Mitsubishi,” Maurer explains.

The Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) that came into effect between Japan and the European Union (EU) in February 2019 is also expected to become a key milestone. This agreement stipulates that, over a period of 16 months, the EU will reduce 99 per cent of its tariffs on Japanese imports, while Japan will reduce 94 per cent of its tariffs on EU imports. For Europe the main priority is agricultural products sent to Japan, whereas the EU will reduce tariffs on Japanese car imports into the EU. Aside from strengthening the trade in goods, the agreement aims to break down non-tariff obstacles in the Japanese market so that EU companies will have more access to public tenders there. “I expect that the EPA will have a positive impact on a variety of transportation projects,” says Maurer. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, he has not yet been able to see any growth in bilateral exports between Germany and Japan. Parallel to this, Germany’s Federal Foreign Office has reported that the trade volume between Germany and Japan increased slightly in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic (2019: 44.7 billion euros), but decreased to 38.8 billion in 2020 due to the pandemic.

High demands and limited capacities

But how to key players feel about the Japanese market and latest developments? LOGISTICS PILOT spoke with experts from Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (MOL) and Leschaco to find out.

MOL has been active in trade between Germany and Japan since it was founded in 1884. The shipping company, based in Tokyo, and its subsidiaries operate a fleet of more than 700 ships, including car transporters, container ships, bulk freighters and tankers. “As a provider of international maritime transport services for cars and rolling cargo, we currently have about 100 car carriers in operation and are among the global market leaders in this segment,” explains Mario Janssen, General Manager of MOL Auto Carrier Express (MOL ACE). From his office in Hamburg he organises MOL ACE arrivals in Europe, such as in Bremerhaven and Emden, as well as departures to Japan. “We offer regular service from Europe to Japan four times per month. We mainly transport cars from high-end European companies, but also high-and-heavy and project cargo. The heavyweights that the company sends for ro-ro shipments include farming machinery and tractors, heavy-duty modules and reach stackers. Special machines that can’t be constructed in Japan in this manner.

“The coronavirus caused more digitisation in Japan.”

Mario Janssen, General Manager of MOL ACE

More than 5,000 such Leschaco tanks are being moved across the world’s oceans to transport liquid chemicals.

Janssen explains the idiosyncrasies of the Japanese market: “Many products are made locally, and the competition there is great. Also great is the risk of only being one of many at the end of the day. “The customers who use the Japanese market have high standards, especially when it comes to quality and reliability.” Regular departures with mandatory run times are thus crucial. MOL customers in the automotive segment also usually have their own local distribution system within Japan, which includes the ports of arrival. This is pushing MOL ACE further toward approaching these exact locations. These are not the largest container ports in the country, but rather the harbours in Hitachi, Chiba, Yokohama and Toyashi. Nearly half of all automotive transports to Japan went through Toyashi alone. Janssen goes on to explain that the capacities in these ports and terminals are very limited, and so the Japanese recipients of the rolling cargo often transport them further very quickly, usually by lorry. “But that’s not in our jurisdiction anymore. This is done port-to-port and ends with the hand-off and quality check by the recipient,” says Janssen.

“A lot is still done through fax”

Leschaco has also been active in Japan for over 30 years. When the international logistics service provider based in Bremen began to trade tank containers with the Pacific nation in 1987, there was still an on-site representative. Since 1995 the consortium has offered its services in tank container logistics and in the maritime and air freight sectors via its own brand Leschaco Japan, based in Tokyo. It opened its own office in the commercial and port city Osaka in western Japan three years ago. “Since it was founded, Leschaco Japan has continued to grow and was closely linked to the overall growth of our tank container shipping. We had 500 tank containers in the initial years, but now we have 5,000,” says Hans Werner Burg, Managing Director of Leschaco Japan. Leschaco transports all sorts of liquid chemicals in these special containers. “The trade with Japan is usually in oil additives and intermediate goods for cleaning agents and shampoos, plastics for the automotive industry and high-end adhesives for glazing,” Burg explains.

As a logistics service provider Leschaco manages all door-to-door transportation to the Land of Smiles – chiefly maritime, but also by air. Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe are the main destination ports for the former. “The customer decides what happens next,” explains Burg. “We also offer the option of delivering to smaller, local ports with feeder ships.” After arrival and customs at the port, the next step is lorry delivery to the destination. “Railways in Japan don’t play as big a role for imports and exports as they do in Germany, so generally we only use them for transferring empty containers,” he explains. Then he gives LOGISTICS PILOT some surprising information that one might not expect from a tech-friendly country like Japan. “Personal stamps and fax machines are still used a lot here. Some customs agents still send their receipts via fax. But the coronavirus has caused an increase in digitisation in the Japanese logistics sector.”

Digitisation is paramount

This lines up with GTAI expert Maurer’s own experience. He explains: “Digitisation will have to take place in a functioning Japanese transportation and logistics market in the future. The country’s global trade flows make it imperative that the structures become more streamlined, as the coronavirus has shown.” At the same time, he says, the pandemic has made it apparent that supply chains must be secured and that there is no way around instruments like Big Data or blockchain technology. “The market researchers at Fuji Keizai predict that the market for next-gen logistics systems will double to 8.5 billion US dollars by 2025. Ultimately there will be a high degree of automation along the entire supply chain, meaning that warehouses or lorries will be leased or used as part of a sharing model,” Maurer says, outlining a possible future scenario. (bre)

Logistics Pilot

The current print edition - request it now free of charge.

“Rail transit is not as important in Japan.”

Hans Werner Burg, Managing Director Leschaco Japan

Makoto Sekikawa, Lower Saxony Representative in Japan

“Raising awareness of Lower Saxony’s potential in Japan”

Lower Saxony opened a representative office in Japan in April 2020. The office is located in the capital city of Tokyo, where the five major trade and travel routes to every region in Japan began 150 years ago. With help from the local team, the economic partnership between Lower Saxony and Japan can be further expanded. Specifically this means marketing Lower Saxony in Japan as an economic and investment location, showing Japanese companies the potential for cooperation and investments in the German state of Lower Saxony, and helping companies from Lower Saxony gain a footing in the Japanese market.

“The Japanese are familiar with companies like Volkswagen and Continental, but Lower Saxony has more to offer than the world-famous auto industry. The office hopes to raise awareness of all the potential that the Lower Saxony economy holds in other segments like life science, energy or food manufacturing, and to give Lower Saxony the image of an innovative location in Japan,” says Makoto Sekikawa, Lower Saxony Representative in Japan.

For example, Germany’s second largest state by area could use the topic of sustainability to incentivise Japan, which hopes to become greenhouse gas-neutral by 2050. After all, one out of every five wind power plants in Germany is located in Lower Saxony. 88 per cent of the power consumption in Lower Saxony is already generated from renewable energy, and it is the first state in the world to use fuel cell engines for regular train transit. Yet Lower Saxony can also learn from a variety of pioneering projects in Japan, such as for transporting liquid hydrogen, or hydrogen in the form of methylcyclohexane imported from Brunei. Such technology may also be of interest for ports in Lower Saxony.

“One major focal point is the initiation of partnerships for economic research and development, because both countries are faced with the same challenges such as decarbonisation of the energy industry and an ageing population. With the Lower Saxony Office in Japan and the desired closer cooperation, these topics can be approached by both sides,” Sekikawa explains.

Unfortunately for the team in Tokyo, the office opened right in the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, severely inhibiting its activities. But the time was used to present Lower Saxony and its strengths, and make important contacts, through webinars and virtual conferences. Yet these measures are to be expanded once the circumstances allow for it.

“Nothing is left to chance”

DB Schenker has been involved in logistics for the Olympic Games in a variety of ways since 2000. Tokyo 2021 has its own unique challenges.

The Olympics and Paralympics will be held in Tokyo this July and August, but without any fans from overseas due to the pandemic. But DB Schenker Deutschland will be there as an official partner of the Tokyo 2020 Germany Team, and as an exclusive logistics partner for Deutsches Haus Tokio 2020. DB Schenker Sport Events will also process all cargo for the German Olympics delegation, as commissioned by the German Olympic Sports Federation (DOSB) and National Paralympic Committee Germany (DBS). The logistics experts will organise transportation of training and competition equipment for the German athletes, as well as their physical therapy materials and team medical supplies. These include massage benches, medicine, office materials, sun cream and energy bars, among other things. The experts are also delivering a variety of media equipment and event technology to Japan, from the cables to massive monitors and communication tools.

“It’s important to us that nothing is left to chance.” Only then can we ensure that everything is delivered and assembled on time. We often only have a brief window of time to transport training and competition equipment,” says Stephan Schmidt, Director of Sports Events Germany at DB Schenker. This makes it all the more helpful that the DB subsidiary can draw on its many years as a service partner of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) and its experience as a strategic partner of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) from 2003 to 2008. With this wealth of experience under the company’s belt, Stephan Schmidt knows that long-term preparation with an “after the game is before the game” approach is especially crucial to such a big event. Planning of the details begins with the DOSB and DBS around nine months before the games begin. The logistics needs of the individual associations are determined, freight space is booked, customs matters are resolved and the the appointments for pick-up and delivery are coordinated. The logistics for the teams’ attire are always a big highlight. “We pack one travel bag of official clothing for each athlete. Then of course there is the various sports equipment, the transportation of which is quite challenging from a logistics perspective. For the Olympic Games in Tokyo the main issue is definitely the row boats, which we’re sending to Tokyo by air,” explains Stephan Schmidt. For transporting materials from Europe to Japan, DB Schenker follows a dual carrier approach: Products with looser time requirements are sent by maritime freight, while critical or particularly valuable equipment, such as for televisions, is sent by air.

But when it comes to its current work for the Olympics, DB Schenker works on the national and international levels. For example, Schenker’s offices in Belgium, Italy, Cuba, Norway, Great Britain and Switzerland tend to the logistics for “their” respective Olympic teams. Some of them also work with “their” participants in the Paralympics. The country offices in Belgium, Croatia and Great Britain are also in charge of “their” guest house logistics, including provisions. All of them have a very special hurdle to ovecome for the Tokyo Games: implemending Japan’S coronavirus-induced safety and health requirements as well as those of the local organisation committee from arrival to departure. (bre)

Stephan Schmidt, Director of Sports Events Germany at DB Schenker

Most read

“Sushi there tastes totally different than in Germany”

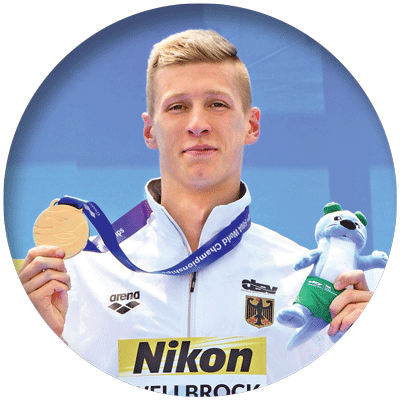

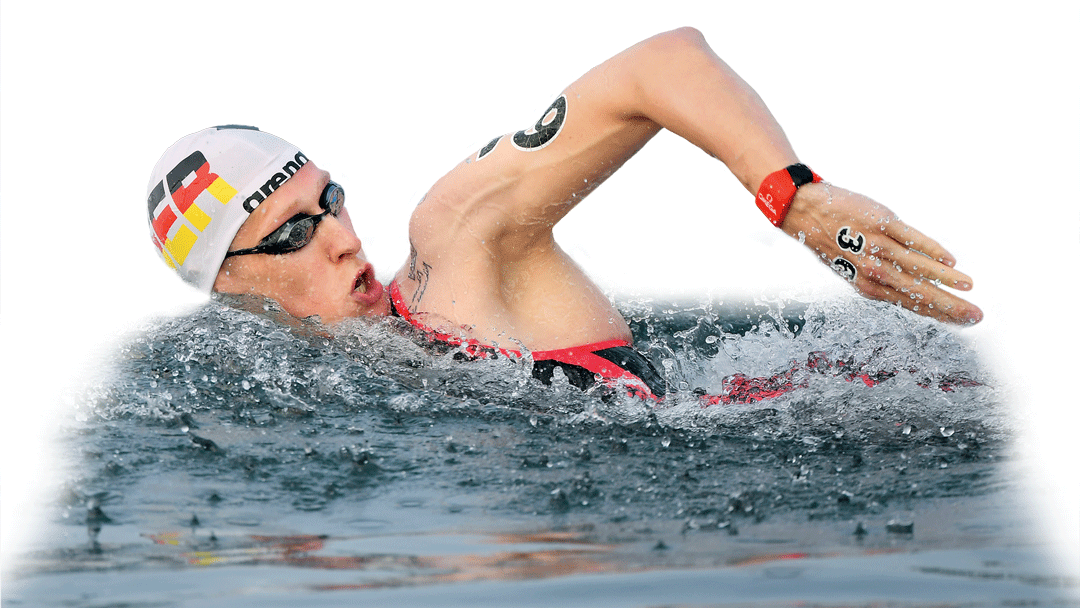

Swimmer Florian Wellbrock is one of the big Olympics hopefuls on the German team in Tokyo. With his titles for the 1500 metre freestyle and ten kilometres in open water, the Bremen native (who starts for SC Magdeburg) became the first swimmer in history to win gold in open water and a pool for a world championship, specifically the 2019 World Swimming Championships in Gwangju.

Mr Wellbrock, what are your expectations for Tokyo in July?

Florian Wellbrock: Mainly I’m looking forward to a nice and safe Olympics. Of course I want to get the best times and stand on the podium. Unfortunately I missed out on that at my first Olympics in Rio de Janeiro in 2016. But my time in Brazil was still an unforgettable experience for me.

How familiar are you with Japan?

Florian Wellbrock: I was in southern Japan once before to train for a competition. While there I learned that the Japanese are a very hospitable and pleasant people. I felt really happy there, and especially enjoyed going out for sushi. Because of the atmosphere it tastes entirely different from how it does in Germany.

How do you, as an athlete, feel about the decision to hold the Olympics as they are planned during the pandemic?

Of course I can understand the pros and cons of it. But the Olympics are really special to us athletes. They only take place every four years, and for me they’re much more than just a big competition. Fairness and tolerance are the core values. That makes it so unique, competing with the best of the best around the world. The media attention is also extremely important to athletes. Many sports only get to present themselves to the world every four years. This year will be much different from others because of the pandemic. The top priority is the health of all athletes and everyone involved. So I’m hoping for a safe arrival, a good hygiene plan, and most importantly, great games.

As a native of Bremen, do you have connections to the harbour or the maritime industry?

Yes, as a kid I spent a lot of time with my parents on our small leisure boat. So I knew not just the harbour in Bremen, but many other ports throughout northern Germany. I’m still especially impressed that giant container ships can even float. Those giants looked a lot bigger to me when I was a child, of course, even though the biggest ones back then couldn’t even hold over 20,000 containers, unlike the ones that are around now.